Alarcon, Vernadeth B.

Alarcon, Vernadeth B.Affiliation: School of Medicine, Institute for Biogenesis Research

Position: Associate Professor

Degree: PhD (University of Toronto, Canada)

Phone: (808) 692 1417

Fax: (808) 692 1962

Email: vernadet@hawaii.edu

Address: 651 Ilalo St., Biosciences Building, Room 163J/H, Honolulu, HI 96813

Preimplantation embryo, Cell lineage, Cell polarity, Developmental toxicants

Mammals, such as ourselves, are unique among other organisms in that our embryonic phase needs to implant into the mother's uterus and create the placenta to allow further development. To achieve such unique style of development, we have evolved to generate a special type of cells, called the trophectoderm, during the very early stages of embryo development (Figures 1 and 2). Trophectoderm is dedicated for implantation and placenta formation. In fact, the first and critical decision that embryonic cells must make after fertilization is whether they commit to become part of the future body or the trophectoderm, i.e., the precursor of placenta. This first decision needs to be controlled very carefully in a balanced manner because embryos cannot survive or develop further if one cell type (either "future body cells", called the inner cell mass, or "future placenta cells", the trophectoderm) is not generated sufficiently.

Our lab's research goal is to uncover the molecular mechanisms that control this early cell type decision-making, using mouse embryos as well as mouse and human cell lines. We have identified candidate genes, including cell polarity regulators (e.g., Alarcon 2010; Kono et al. 2014), and we are testing their roles in the embryo. We employ various experimental approaches, such as in vitro embryo culture, microinjection of the embryo, chimera production, embryo transfer into surrogate mother's reproductive tract, and cell and molecular biology techniques. Understanding the mechanisms of cell type decision-making in the early embryo has applications in the treatment of infertility, especially in ART (assisted reproductive technologies). Our findings have potential to serve as a basis for improving in vitro culture conditions of human embryos and for identifying healthy embryos for uterine transfer to produce successful pregnancies.

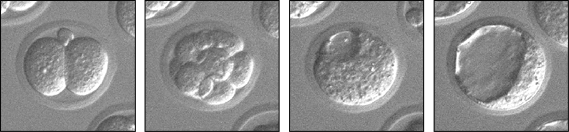

Figure 1: A preimplantation mouse embryo developing over time (left to right): 2-cell, 8-cell, early blastocyst, and late blastocyst. In the late blastocyst, cells have committed to the trophectoderm (future placenta) and inner cell mass (future body) lineages. Live development in vitro was recorded for three days, using time-lapse video microscopy.

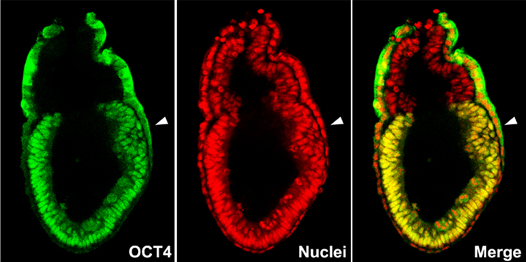

Figure 2: Immunofluorescently stained blastocysts, showing expression of transcription factors essential for cell-type commitment. (A) OCT4 (green) protein is localized in inner cell mass. (B) CDX2 (yellow) protein is localized in trophectoderm. Nuclei are stained red with propidium iodide. Images were taken using confocal microscopy.

Richard Allsopp

Richard AllsoppAffiliation: School of Medicine, Institute for Biogenesis Research

Position: Assistant Professor

Degree: PhD

Phone: (808) 692 1412

Fax: (808) 692 1951

Email: allsopp@hawaii.edu

Address: 651 Ilalo St., BSB 163B, Honolulu, HI 96813

Analysis of the role of telomerase in stem cells and human diseases.

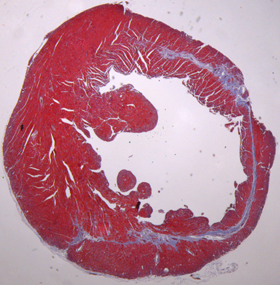

Telomerase is required to maintain telomeres, the protective cap at the end of chromosomes, in all eukaryotic cells. In mammals, including humans, some somatic cells in adults lack telomerase, and as a consequence, telomeres gradually short during cell division and as a function of age. Stem cells are required to replenish dead or damaged cells throughout life, and therefore telomerase is thought to play an important role in stem cell survival. While telomerase is indeed detectable in many types of human stem cells (unlike mature somatic cells), in some cases, such as in the blood, there isn't sufficient telomerase to maintain telomere length as these cells divide, and as a consequence, telomeres shorten in all blood cells during aging. On the other hand, male germ cells do have sufficient telomerase to thwart telomere loss during aging. one of the primary goals in my lab is to get a better understanding as to how telomerase activity levels are regulated in different types of stem cells. Recently, we have performed a screen for transcriptional regulators in embryonic stem cells and found that the transcription factor Hypoxia Inducible Factor 1 alpha (Hif1alpha) is essential for maintainence of functional levels of telomerase in these cells. One of the future goals of our work is get a better understanding as to the role of Hif1alpha in regulating telomerase in other types of stem cells. My lab is also interested in evaluating the therapeutic potential of using stem cells, particularly stem cells derived from the bone marrow, which is a pracxtical source of stem cells in adults, to treat cardiac infarcts using a murine model system.

Ben Fogelgren

Ben FogelgrenAffiliation: School of Medicine, Department of Anatomy, Biochemistry, and Physiology

Position: Assistant Professor

Degree: PhD (University of Hawaiʻi)

Phone: (808) 692-1420

Fax: (808) 692-1951

Email: fogelgre@hawaii.edu

Address: 651 Ilalo St., BSB 110, Honolulu, HI 96813

Molecular mechanisms of primary cilia assembly and signaling.

Genetic regulation of kidney development, physiology, and disease.

Our research is focused on the molecular and genetic causes of abnormal kidney development, as well as the novel causes and treatments of adult renal diseases such as polycystic kidney disease and acute renal injury. The same molecular signals and cellular morphogenesis patterns that we study in the kidney can also give us novel insights into development of other tissues, as well as teach us how these processes can be disrupted in a large variety of diseases.

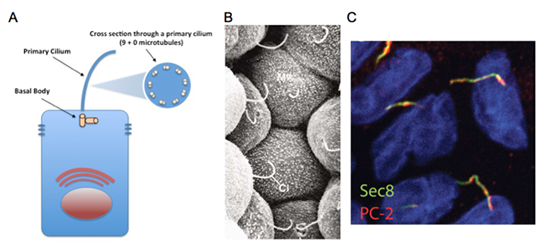

Cysts and tubules are primary building blocks of the kidney, and defects in cystogenesis or tubulogenesis during kidney development can result in a spectrum of pediatric and adult renal diseases. Relevant to our research, during kidney development, disruption in the formation of de novo epithelial cysts from pools of mesenchymal stem cells lead to various forms of congenital abnormalities such as kidney hypoplasia, dysplasia, or agenesis. On the other hand, following nephrogenesis, when the inhibitory signals that halt excessive cyst formation are disturbed, forms of renal disease such as polycystic kidney disease (PKD) can occur. Autosomal dominant PKD (ADPKD), which affects approximately 500,000 Americans and currently has no approved treatment, is the most common potentially lethal genetic disease. Every variation of human PKD has been attributed to mutations in genes important to the assembly or function of the primary cilium, a thin rod-like organelle on renal tubular epithelial cells which projects into the tubular lumen (See Figure 1).

Primary cilia have been found on the surface of most growth-arrested or differentiated mammalians cells, including a large variety of epithelial cells, endothelial cells, connective-tissue and muscle cells, as well as neurons and even embryonic stem cells. Although the presence of primary cilia has been noted for over a hundred years, its biological function was a mystery. Due to an exploding volume of research in just the last decade, it is now believed the primary cilium acts as a "sensory antenna" to relay signals to the cell based on the extracellular environment. These can include sensory clues such as mechanical stimulation (bending or rotation), chemosensation (detection of growth factors, morphogens, etc.), osmolarity, light, temperature, and even gravitational pull. It is thought that primary cilia along the renal tubules are responsible for detecting fluid composition and flow dynamics, and when defective, the cells misinterpret this as a signal to dedifferentiate and proliferate, resulting in the formation of large pathogenic renal cysts. However, defects in primary cilia can affect other tissues as well, and have resulted in a new classification of human disorders termed "ciliopathies".

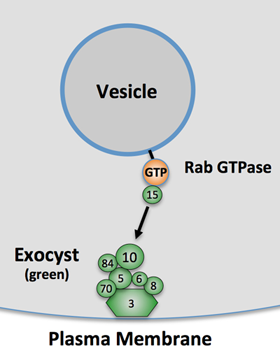

Currently, we have research projects focused both on the molecular mechanisms of de novo cyst formation, and on primary cilia assembly and signaling. We have found both of these cellular activities depend on the exocyst complex, a highly conserved eight-protein complex (see Figure 2), which is involved in targeted secretory vesicle transport. We are working hard to discover how cells regulate the exocyst subunits in order to direct polarized trafficking to specific locales such as primary cilia and the lumens of growing epithelial cysts. These discoveries may lay the groundwork for novel therapies for adult and pediatric renal diseases, and expand our knowledge of some of the basic cellular and molecular mechanisms by which the human body controls its development.

Affiliation: School of Medicine, Department of Anatomy, Biochemistry, and Physiology

Position: Assistant Professor

Phone: (808) 692-1009

Fax: (808) 692-5497

Email: jkenjih@hawaii.edu

Address: 651 Ilalo St., MEB 307R, Honolulu, HI 96813

Affiliation: School of Medicine, Department of Anatomy, Biochemistry, and Physiology

Position: Professor

Phone: (808) 692-1442

Fax: (808) 692-1951

Email: lozanoff@hawaii.edu

Address: 651 Ilalo St., BSB 119A, Honolulu, HI 96813

Yusuke Marikawa, PhD

Yusuke Marikawa, PhDAffiliation: School of Medicine, Institute for Biogenesis Research

Position: Associate Professor

Degree: PhD (Kyoto University, Japan)

Phone: (808) 692-1411

Fax: (808) 692-1962

Email: marikawa@hawaii.edu

Address: 651 Ilalo St., BSB 163A, Honolulu, HI 96813

Axis Specification and Germ Layer Formation in Mammalian Embryos.

Differentiation and Morphogenesis in Pluripotent Stem Cells.

Stem Cell-Based Detection of Teratogens.

How can a single cell, like the fertilized egg, transform into a complex architecture, like our body? With respect to this biggest question of Developmental Biology, my lab is currently conducting research projects under the following two main themes:

"Axis Specification and Germ Layer Formation in Mammalian Embryos"

Soon after implantation, the embryo of human or mouse is a single layer of epithelial tissue, called the epiblast. Later, one edge of the epiblast forms the structure called the primitive streak, from which cells migrate away to form new tissue layers. This event, i.e., the formation of the primary germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm), is the first step towards the generation of complex body patterns. Furthermore, the primitive streak formation is the first morphological landmark of body axis specification, as it establishes the caudal end of the future body.

Activation of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling, an evolutionary conserved signal transduction machinery, is the key to the formation of the primitive streak in the epiblast. The specific questions that are addressed in my current projects are:

1) How Wnt/beta-catenin signaling is activated in a localized region of the epiblast?

2) What genes are turned on by Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in the primitive streak?

3) How can cells in the primitive streak transform from epithelial into migratory state?

"Differentiation and Morphogenesis in Pluripotent Stem Cells"

Embryonic stem (ES) cells and induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells can be maintained and propagated in a culture dish as undifferentiated cell populations, which are very similar to early embryonic cells before germ layer formation. Because studies of mammalian embryos are often hindered by the unique reproductive mode of mammals (i.e., embryos normally develop in the uterus), pluripotent stem cells, like ES and iPS cells, can serve as great in vitro models, which can be experimentally manipulated more easily. Furthermore, these pluripotent stem cells offer tremendous promise for the future regenerative medicine, as they can be used to derive various types of functional tissues in vitro, and those stem cell-derived tissues may be used for tissue replacement therapy and drug screening.

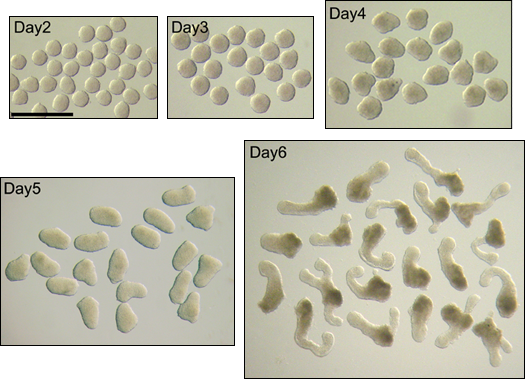

The goal of my lab is to elucidate molecular and cellular mechanisms of differentiation (e.g., of mesoderm and endoderm tissues) and morphogenesis (e.g., of tissue elongation along the body axis) using mouse and human pluripotent stem cells.

Takashi Matsui

Takashi MatsuiAffiliation: School of Medicine, Dept. of Anatomy, Biochemistry and Physiology, Center for Cardiovascular Research

Position: Professor and Chair

Degree: MD and PhD (Jikei Univ Sch of Med, JAPAN)

Phone: (808) 692-1554

Fax: (808) 692-1973

Email: tmatsui@hawaii.edu

Address: 651 Ilalo St., BSB 110, Honolulu, HI 96813

The role of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) in the heart, Cardiac cell signaling controlling cell survival, Diabetic hearts, Ferroptosis

Our research is focused on the insulin signaling pathway in cardiomyocytes, especially cardioprotective effects against pathological settings such as ischemia. Our interests center around the role of the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), which is intimately related to the insulin/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt signal transduction pathway. In order to investigate the role of mTOR in the heart, we utilize a variety of in vitro, in vivo, and ex vivo models of heart failure with genetically manipulated models of mTOR such as transgenic and knockout mice. We have reported that the role of cardiac mTOR in prevention of cardiomyocyte cell death that arises from myocardial infarction and cardiac hypertrophy, apparent risk factors for heart failure.

Diabetes is an independent risk factor for both heart failure and ischemic heart disease. Because of the important role of mTOR in insulin signaling, we have been working to determine the role of mTOR in diabetic hearts, and exploring the mTOR signaling pathway as a novel therapeutic target for treatment of heart failure in diabetes.

We recently demonstrated that mTOR is necessary and sufficient for cardiomyocyte protection against iron-mediated cell death that includes excessive iron-induced cell death and ferroptosis that is an iron-dependent form of regulated cell death. This is the first report that ferroptosis is a significant type of cell death in cardiomyocytes. We are currently defining the pathophysiological role of ferroptosis in cardiac diseases such as acute myocardial infarction and heart failure.

Alika K. Maunakea, Ph.D.

Alika K. Maunakea, Ph.D.Affiliation: School of Medicine, Department of Native Hawaiian Health

Position: Associate Professor

Graduate Faculty: Molecular Biosciences and Bioengineering (MBBE)

Developmental and Reproductive Biology (DRB)

Cell and Molecular Biology (CMB)

Neuroscience Specialization Program

Phone: (808) 692-1048

Fax: (808) 692-1255

Email: amaunake@hawaii.edu

Address: 651 Ilalo St., Room 222K, Honolulu, HI 96813

Stefan Moisyadi, PhD

Stefan Moisyadi, PhDAffiliation: School of Medicine, Institute for Biogenesis Research

Position: Associate Professor

Graduate Faculty: Developmental and Reproductive Biology (DRB)

Cell and Molecular Biology (CMB)

Phone: (808) 956-3118

Fax: (808) 956-7316

Email: moisyadi@hawaii.edu

Address: IBR, 1960 East-West Rd. Room E108, Honolulu, HI 96822

Affiliation: School of Medicine, Anatomy, Biochemistry & Physiology

Position: Assistant Professor

Phone: (808) 692-1422

Fax: (808) 692-1951

Email: polgar@hawaii.edu

Address: 651 Ilalo St., BSB 110, Honolulu, HI 96813

Kathryn J. Schunke

Kathryn J. SchunkeAffiliation: Department of Anatomy, Biochemistry and Physiology, Center for Cardiovascular Research, Diabetes Research Center, John A. Burns School of Medicine

Position: Assistant Professor

Degree: PhD

Phone: (808) 692-1565

Email: kschunke@hawaii.edu

Address: 651 Ilalo St., BSB 211, Honolulu, HI 96813

Johann Urschitz, PhD

Johann Urschitz, PhDAffiliation: Institute for Biogenesis Research Department of Anatomy,

Biochemistry and Physiology, John A. Burns School of Medicine

Graduate Faculty: Developmental and Reproductive Biology (DRB)

Cell and Molecular Biology (CMB)

Phone: (808) 956-7417

Fax: (808) 956-7316

Email: johann@hawaii.edu

Address: IBR, 1960 East-West Rd., Room E112, Honolulu, HI 96822

Monika A. Ward, PhD

Monika A. Ward, PhDAffiliation: Institute for Biogenesis Research Department of Anatomy, Biochemistry and Physiology, John A. Burns School of Medicine

Graduate Faculty: Chair, Developmental and Reproductive Biology (DRB)

Cell and Molecular Biology (CMB)

Phone: (808) 956-0779

Fax: (808) 956-7316

Email: mward@hawaii.edu

Address: IBR, 1960 East-West Rd., Room E104, Honolulu, HI 96822

W. Steven Ward, PhD

W. Steven Ward, PhDAffiliation: Institute for Biogenesis Research Department of Anatomy, Biochemistry and Physiology, John A. Burns School of Medicine

Graduate Faculty: Developmental and Reproductive Biology (DRB)

Cell and Molecular Biology (CMB)

Phone: (808) 956-5189

Fax: (808) 956-7316

Email: wward@hawaii.edu

Address: IBR, 1960 East-West Rd., Room E108, Honolulu, HI 96822

Yukiko Yamazaki, PhD

Yukiko Yamazaki, PhDAffiliation: Institute for Biogenesis Research Department of Anatomy, Biochemistry and Physiology, John A. Burns School of Medicine

Graduate Faculty: Developmental and Reproductive Biology (DRB)

Cell and Molecular Biology (CMB)

Phone: (808) 692-1416

Fax: (808) 692-1962

Email: yyamazak@hawaii.edu

Address: 651 Ilalo St., BSB 163-3 Honolulu, HI 96813

Yiqiang Zhang

Yiqiang ZhangAffiliation: JABSOM, Center for Cardiovascular Research

Phone: (808) 692-1480

Fax: (808) 692-1973

Email: yiqiang.zhang@hawaii.edu

Address: 651 Ilalo St., BSB-311D, Honolulu, HI 96813

Peter R. Hoffmann, PhD, MSPH

Peter R. Hoffmann, PhD, MSPHpeterrh@hawaii.edu | (808) 692-1510

Full Member, Cancer Biology Program, University of Hawaiʻi Cancer Center

Academic Appointment(s): Professor, Cell and Molecular Biology Department, John A. Burns School of Medicine, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa

Degree(s): PhD, Immunology and Microbiology, University of Colorado

MSPH, Public Health, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa

Thomas Huang, PhD

Thomas Huang, PhDAssociate Professor

Affiliation: JABSOM, Obstetrics, Gynecology and Women's Health

Email: huangt@hawaii.edu

Phone: (808) 203-6533

Fax: (808) 955-2174

Address: Kapiolani Med Ctr

Olivier Le Saux, Ph.D.

Olivier Le Saux, Ph.D.Professor and Chair, Department of Cell and Molecular Biology (CMB)

Area of Expertise: Skin and cardiovascular diseases, ectopic calcification

Email: lesaux@hawaii.edu

Phone: (808) 692-1504

Birendra Mishra PhD, MS, DVM

Birendra Mishra PhD, MS, DVMAssistant Professor

Department of Human Nutrition, Food & Animal Sciences, College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources – University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa

Email: bmishra@hawaii.edu

Phone: (808) 956-7021

Fax: (808) 956-4024

Jesse B. Owens, PhD

Jesse B. Owens, PhDAffiliation: Institute for Biogenesis Research

Department of Anatomy, Biochemistry and Physiology

John A. Burns School of Medicine

Graduate Faculty: Developmental and Reproductive Biology (DRB)

Cell and Molecular Biology (CMB)

Phone: (808) 956-4828

Fax: (808) 956-7316

Email: jbowens@hawaii.edu

Address: IBR, 1960 East-West Rd, Room E108, Honolulu, HI 96822

Michelle Tallquist, PhD

Michelle Tallquist, PhDAffiliation: JABSOM, Center for Cardiovascular Research

Position: Associate Professor

Degree: PhD (Immunology, Mayo Clinic and Foundation)

Phone: (808) 692 1579

Fax: (808) 692 1973

Email: michelle.tallquist@hawaii.edu

Address: BSB 311E, 651 Ilalo Street, Honolulu HI, 96813

Jinzeng Yang, PhD

Jinzeng Yang, PhDAffiliation: Department of Human Nutrition, Food and Animal Sciences

Position: Associate Professor

Degree: PhD (University of Alberta, Canada)

Phone: (808) 956 6073

Fax: (808) 956 4024

Email: jinzeng@hawaii.edu

Address: 1955 East West Road, Rm 216, Honolulu, HI 96822

Affiliation: Geriatric Medicine

Position: Professor

Phone: (808) 523-8461

Fax: (808) 528-1897

Email: willcox@hawaii.edu

Address: Kuakini Med Ctr HPM-9

Michael Ortega, PhD

Michael Ortega, PhDPrincipal Investigator

Phone: (808) 691-7902

Fax: (808) 691-7939

miortega@queens.org

Claire Wright, PhD

Claire Wright, PhDSenior Director, Office of Sponsored Programs

Associate Professor, Biology

School of Natural Science and Mathematics

Email: claire.wright@chaminade.edu

Phone: (808) 739-8343